by Rozanna Weinberger

The other day a colleague was warming up beautifully on a violin I was showing him. I remember being impressed at the fluidity of his technique, which seemed confident and inspired. When he stopped I praised him and then said I would like to shoot a little demo video clip of him playing since the sound was so lovely and a wonderful representation of the instrument. No sooner did I make that request than everything changed in my friends demeanor. He needed to ‘warm up’ which I couldn’t quite understand since he had already been playing for awhile and sure enough, the effortlessness playing I had heard use moments before became fraught with uncertainty and mistakes I hadn’t heard previously.

What is it that happens to string players that makes everything change in a pressure situation? Why is that passages that seemed to be perfected in the practice room – when under the gun- prove unreliable? In some cases I’ve seen the most naturally musical players lose their ability to communicate their musical intentions when they think they believe they are limited by the tools of their technical ability or overly focused on the technical side of playing. Sure we all have to build technical skill but very often when players are focused on the musical intent, their bodies naturally produce the requisite movements to execute that musical idea.

Its not uncommon for string players to practice for hours on end, often repeating certain

Batting Average When It Counts Awhile back I coined the idea of technical mastery in performance being akin to a baseball players’ batting average. We are able to, overtime assess the likelihood of a batter being able to hit that ball effectively. I wonder if players have ever tested how many times they are able to play a technical passage accurately when repeating it 5 or even 10 times in a row.

passages hundreds if not thousands of times over the course of learning a piece of music. And yet how many times do we find that when we’re under the gun in front of an audience something happens. Its as if all that practicing is forgotten and the physical experience is completely different. If thats not bad enough we may be pervaded by an inner voice reminding us of all the technical challenges ahead often with a fearful anticipation.

Sure experts can explain away adrenaline and other factors influencing the brain when a pressured situation comes up. But truly there is so much the player can do in the practice room, through CULTIVATING AWARENESS, which can be the basis of overcoming technical/emotional patterns that are likely to manifest under pressure. By awareness, we are talking about a subtle, almost meditative state in which the player learns to observe what the body is communicating to the brain so that learning takes place.

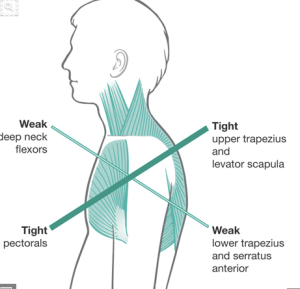

Its also essential that the player develop a refined sense of what their bodies are doing. It really amazes me when I come across players who have ‘suddenly developed carpal tunnel syndrome, or some other similar ailment, which should have been producing pain and tension in the effected areas for months prior because it really does require a lot of physical abuse of a particular muscle or ligament to eventually produce a chronic condition like carpal tunnel.

Why Trying To Copy A Teacher Isn’t The Most Complete Way To Learn – If only an ideal technical command was as simple as copying what a teacher does with reinforcement through practice. Sure many teachers teach that way and many students try to copy what they see their teachers do. In theory this approach seems to make sense, and yet it is one very big reason players develop physical habits that can lead to big problems down the road. This is because unless our own bodies and kinesthetic awareness can help us fine tune our movements, there will remain a level of crudeness to our approach if we don’t make our technique ‘our own’. By this I am referring to the ability to learn from the physical sensations of a movement, whether they give a feeling of prolonged tension that leads to physical pain, or a pattern of movement that does not use the joints efficiently.

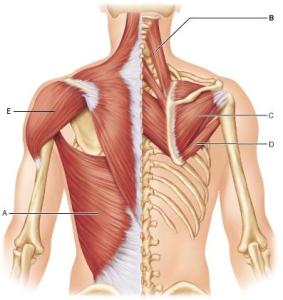

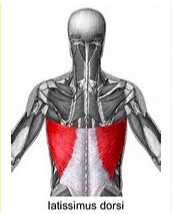

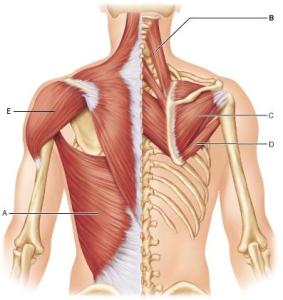

For example, most players don’t connect the movements of the bow arm to the lower back and momentum produced by the weight of the hips but its really true. It is actually possible to play a whole bow from frog to tip using the movements of the torso and back entirely, without ever engaging the arm. While it certainly is convenient to use the arm, players need to discover the momentum that comes from other parts of the body, such as the back & hip.

BOW ARM AWARENESS STUDIES

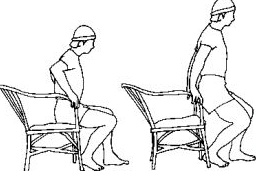

Here is a simple study to cultivate awareness of hips, back & arms in essential bowing. Sitting in a chair, position oneself squarely, with hips aligned to shoulders. By ‘scanning the body’ one may notice what they weight feels like from our hips and bottom in relation to the chair.

1. Notice each hip and observe whether it feelings like one side is pressing into the chair more than the other.

2. Notice the effect this weightiness effects the angle of the shoulders and the head. 3.Does the head tend to tilt in the same direction of the favored hip or in the opposite direction?

Observations on the bow ‘arm’.

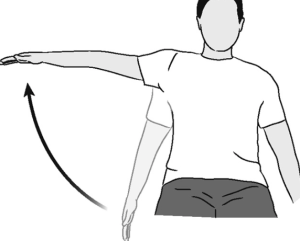

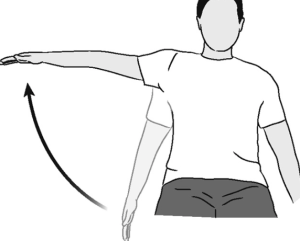

- While still sitting in the chair, bring the right hand up to the left shoulder. Swing the hand/arm backwards as far as the arm can go then bring hand back to the shoulder. This step can be repeated and if arm feels slightly fatigued, allow arm to fall back down to side and relax.

- Bring right hand back up to the left shoulder in ‘chicken wing’ type position once again. This time, while keeping hand on shoulder turn the shoulders and upper body to the right so that whatever is to the right of oneself can be viewed. Then allow body to swivel back to original position. While repeating this movement slowly notice how the spine is effected. Where does the movement seem most active? What part of the spine does this occur? After a couple repetitions, rest.

- Bring right hand back to left shoulder. This tie player will turn to the right using only the waist & hips to turn. Again notice the sensations in the spinal chord as well as the hips. What happens to the weight of the body as one is turning? Are their any parts of the movement that feel tight? Any parts of the spine that are difficult to sense? After repeating a couple times, rest.

- Repeat step 3. But rather than keeping the right hand on the left shoulder the whole time, this time, allow the hand and arm to swing back in response to the movements of the spine & hips.

- Turn the body back towards the left and notice how arm swings back from the momentum of the rest of the body movements.

The right hand atop the left shoulder is similar to arm placement when playing at frog.

As arm is swung to the right, notice what the direction of the left side of the body feels most natural.

Understanding The Right Shoulder: The shoulder is a favored topic because its the source of so much confusion. We are told not to raise the shoulder quite often and yet it is impossible to move the arm & back without the shoulder being engaged in some way. It may take the student months if not years of self discovery until they can feel how the shoulder is a part of the whole. Its not the fulcrum, but it must function in relation to the back and arm. As such the shoulder is elevated but its more a reaction to a circular movement that should be happening in the elbow. The shoulder elevates but then it drops down, and with it the weight of the arm that produces the sound on the string as the bow draws across it. it seems many players can elevate the shoulder, but cultivating sufficient awareness of the shoulder and muscles surrounding it, is necessary to feel the sense of tension and release when the weight of the arm is released as a result of a drop in the shoulder.

The feeling that everything is somehow different from the practice room may very well be an accurate reading when our emotions take over and find expression in exasperating tensions in the body. It may very well be that the excess tension is also manifesting in the practice room but under pressure, manifests to an extreme. There may also be cases where our general technical approach is not optimally efficient movements and the body tries to literally protect itself from the embarrassment of a mistake manifest in ones performance.

“The player of the inner game comes to value the art of relaxed concentration above all other skills; he discovers a true basis for self-confidence; and he learns that the secret to winning any game lies in not trying too hard.”

W. Timothy Gallwey, Inner Game of Tennis

Something So Basic As Learning to Feel Our Bones

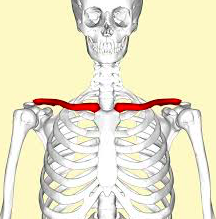

Simple observations of where the humorous bone is in relation to the shoulder girdle and the muscles that may compromise that relation with muscular patterns that are not efficient.

From a technical standpoint, as a frame of reference, most people tend to think about the muscles. But I believe the issues goes deeper to the bones. By developing the sensitivity to differentiate when we are hyper extending our humorous bone in relation to the shoulder girdle, is a pivotal way to begin to use the back when bowing and not just from the arm. All these things can and should be addressed in the practice room. Teachers need to help students discover what can be learned through kinesthetic awareness and the ability to do so will play a pivotal role for the best teachers of performance to come. At the same time the teacher must understand efficient movement sufficient to be able to guide student in differentiating between efficient and inefficient movement, as well as awareness of uncomfortable and excessive muscle movements that can also effect the placement of the bones, the skeleton. And sure, the muscles are indicators of how we move, the skeleton must also be taken into account.

It is the weightiness of the skeleton and its components, and their relationship to each other that creates a natural momentum as well as the weight necessary in the arm, with the help of the back torso and hips, not force, to produce sound. in bow technique. Sure its possible to isolate the arm alone and produce movement and sound, but its also possible to feel the initiation of movement in the bow arm, from the left side of the pelvis and hip – and when that happens, one starts to feel as though the arm is ‘being moved’ rather than initiating movement. Of course, the ideal is when the student comes to discover this possibility for themselves.

Young violinist Alex Cameron discovers musical freedom!

When I was in school I always admired dancers who seemed to be the antithesis of the motley crew which were us instrumentalists. While most string players rarely considered posture as a significant part of the equation for optimal technique, posture and dance technique are inseparable.

When I was in school I always admired dancers who seemed to be the antithesis of the motley crew which were us instrumentalists. While most string players rarely considered posture as a significant part of the equation for optimal technique, posture and dance technique are inseparable.

How do we get the weight of the arm into the string when we are ‘horizontal’ or parallel to the string? The key is to incorporate circular movements with the elbow so the weight, initiated by the elbow goes around, up & down. (Imagine drawing a circle with a pencil attached to the elbow.) This is the optimum movement of the bow arm and conveyer of the weight into the string.

How do we get the weight of the arm into the string when we are ‘horizontal’ or parallel to the string? The key is to incorporate circular movements with the elbow so the weight, initiated by the elbow goes around, up & down. (Imagine drawing a circle with a pencil attached to the elbow.) This is the optimum movement of the bow arm and conveyer of the weight into the string.

by Rozanna Weinberger

by Rozanna Weinberger

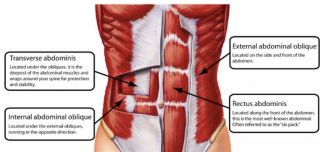

ands press down and push off against the arm rests. Those illusive muscles that enable us to elevate the torso should also be engaged when playing the viola or violin. If these muscles are doing their job, the shoulders will not be as likely to replace this support. Further, the improved posture will support a body angle less likely to cause instrument to fall.

ands press down and push off against the arm rests. Those illusive muscles that enable us to elevate the torso should also be engaged when playing the viola or violin. If these muscles are doing their job, the shoulders will not be as likely to replace this support. Further, the improved posture will support a body angle less likely to cause instrument to fall. cessary trade off for playing a beautiful musical instrument.

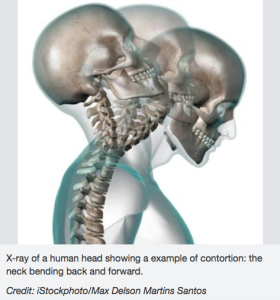

cessary trade off for playing a beautiful musical instrument. Bring the arm down. This time simply bring up the arm in a curved position as if playing the violin. Of course theres no need to raise the shoulder or squeeze the head since theres no instrument to contend with. But imagine if it were possible to play while maintaining a similar feeling of length in the neck and shoulder!

Bring the arm down. This time simply bring up the arm in a curved position as if playing the violin. Of course theres no need to raise the shoulder or squeeze the head since theres no instrument to contend with. But imagine if it were possible to play while maintaining a similar feeling of length in the neck and shoulder!